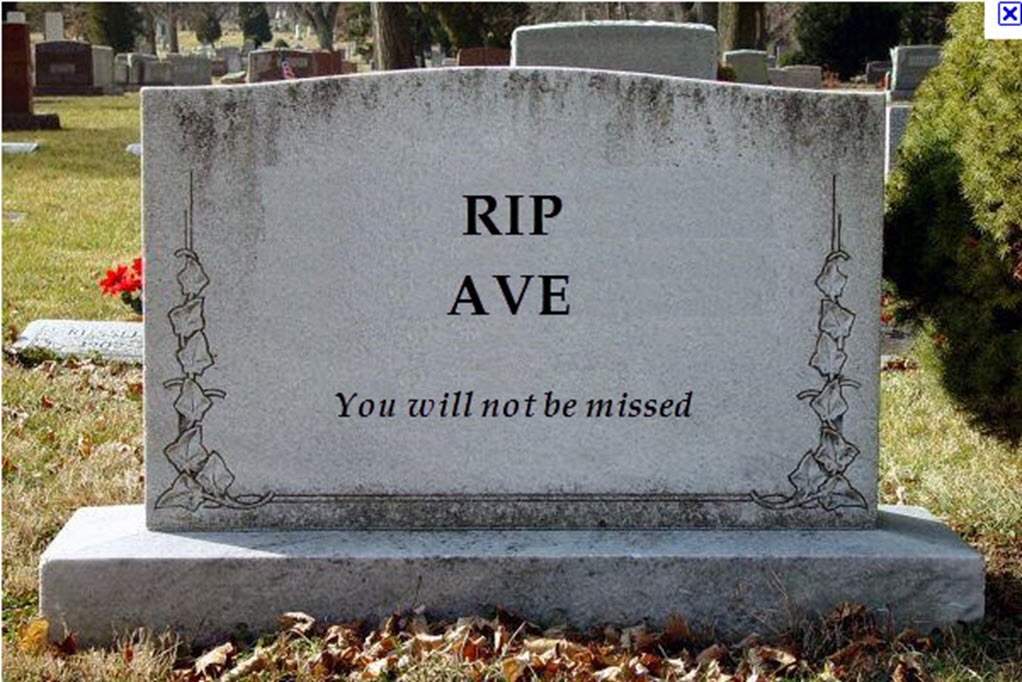

If there’s one phrase guaranteed to generate debate in the PR business, it’s ‘advertising value equivalence,’ AVE for short.

In simple terms, AVE looks at the volume of space an editorial article takes in a print publication, or the amount of time an editorial audio or video segment plays, and equates its value to the price you’d have paid if you had bought the equivalent-size space or time as advertising.

For decades the use of AVE has been a controversial activity, one that has been viewed as unethical by some practitioners and professional associations regarding its perceived lack of validity as a metric to measure the value of a public relations activity.

You can read this argument in considerable detail in a paper published by The Institute for Public Relations. In particular, note this discussion point from the paper:

We urge you to move away as quickly as possible from statements of the nature, “Our news coverage this quarter was worth $X million in advertising.” Instead, talk about how you achieved your prominence goal, how your coverage gained in prominence over the year, or how you beat out your competitors in terms of the prominence of your coverage.

Written in 2003, it still holds credence today.

Last week, the International Association for Measurement and Evaluation of Communication (AMEC) launched what it describes as a global drive for the final eradication of AVE and all of its derivatives as metrics in public relations work.

In AMEC’s announcement, its Chairman Richard Bagnall said, “It’s time AVEs stopped being a talking point in our industry. We will be investing significant time and resource to kill off finally this derided metric.” Bagnall said new industry research showed that client demand for AVEs had dropped from 80% in 2010 to just 18% this year. He added, “Now is the time to kill it off completely once and for all.”

The UK’s Chartered Institute of Public Relations (CIPR) supported AMEC’s announcement with its own pledge to ban AVE:

The CIPR will publish a new professional standard on public relations measurement in the autumn which will identify the use of AVEs in public relations as unprofessional and set out an expectation of members that their use will cease.

The CIPR said that its new guidelines will warn the public about the use of misleading metrics and highlight the role of the CIPR Code of Conduct in raising standards of practice, adding:

[CIPR] Members currently using AVEs will have a period of one year to complete a transition to valid metrics, which the CIPR will support with resources. Members found to be using AVEs thereafter may be liable to disciplinary action.

Such statements from AMEC and the CIPR are a clear signal that actually doing away with AVE in the PR profession is now an act of serious intent. That intent also manifests itself in a significant way in relation to PR awards programmes as noted by AMEC in a list of new initiatives:

Working with PR Award organisers around the world to introduce a zero-scoring policy if awards entries include AVEs as a metric. AMEC members will not provide an AVE as a metric for any award competition entry.

The stage is now set for action by practitioners and associations. Yet I believe the key to success must include how PR academics and clients participate, how they understand the invalidity of AVE and demonstrate their willingness to proactively embrace more credible measurement models such as called for in the Barcelona Principles 2.0.

The final word goes to CIPR President Jason MacKenzie:

It’s time to make a clear and unequivocal statement that AVEs are unprofessional and this is something we intend to communicate to all other Chartered bodies. We believe that other professions represented around the boardroom table will welcome the guidance and grasp that public relations has a more profound impact on business objectives than an artificial measure placed on the value of coverage.

(AVE tombstone at top via AdWeek. Read their post from November 2013 – a valid reality perspective.)

[Updated May 24] The CIPR’s statement on potential disciplinary action against members who continue to use AVE has garnered comment and criticism, not least from a recent past CIPR President, Stephen Waddington.

In “Carrot not stick on AVE,” a blog post published yesterday, Waddington cautions, “It’s a bold move but I fear that it will stigmatise up to a third of the CIPR’s membership,” noting:

Here’s the issue. You don’t need a licence to work in public relations.

While the CIPR is a standard bearer for best practice in public relations in the UK and further afield, it is not a watchdog and has no regulatory authority.

Rather than waving a big stick, Waddington instead advocates supporting practitioners to make the case for alternative forms of measurement to clients and management. “I urge the CIPR board and council to re-evaluate its position otherwise its disciplinary committee is set to be very busy in 2018,” he says.

On LinkedIn, some vibrant discussion is going on in a comment thread to a post by John Harrington, deputy editor at PR Week, on a report in that publication about AMECs and the CIPR’s announcements.

The content on LinkedIn is within the social network’s walled garden (you’ll have to sign in to see it) so I won’t name any commenters here. But here’s a selection of comments thus far:

“This is a shock to the system that was needed. AVE is meaningless. So this is good. It will drive change.”

“I’m not convinced it’s Agencies who are hanging onto AVE.s In my experience it’s global clients who need a simple snapshot for reporting back to HQ.”

“This feels like meaningless posturing until the CIPR can explain how this will be policed and whether there will be an expectation on agencies to act as whistleblowers on clients that are shackled by archaic measurement practices.”

“No-one on this thread (or anywhere else, that I can see) thinks AVEs are good, but we, as an industry, have been hand-wringing, deliberating and agonising for years.”

“My personal conviction is that if a practitioner knows that AVEs are wrong, and persists in their use without acting professionally and challenging the request to apply them, then there’s a problem.”

“Some clients still use AVEs as a measurement of the effectiveness of PR.”

Undoubtedly the debate will widen and it looks set to be a major talking point within the PR industry in the months ahead.

Don’t be surprised if the topic of licensing of PR practitioners rears its head in parallel. Again.

3 responses to “The end of AVE in PR?”

If PR wants to be considered to be a profession it needs to act like one. A doctor prescribes treatment on the basis of effectiveness, not on a metric that happens to suit the patient (or the patient’s accountant). If your job is to win a football match it is not very helpful to report the result in terms of tries converted or wickets taken…

Thanks for adding that perspective, Philip. I like the CIPR’s approach: “Public relations has a more profound impact on business objectives than an artificial measure placed on the value of coverage.” That’s how to educate PRs about more credible ways to measure the worth of PR.

[…] Related: The end of AVE in PR? […]