In the small hours of this Sunday, 31 March, across the United Kingdom and the European mainland, an age-old ritual unfolded almost magically. In unison at 1 a.m. GMT/UTC, as if by the command of Chronos himself, we have “sprung forward,” adjusting our clocks and watches to steal an hour from the morning and gift it to the evening.

As we bask—or perhaps balk—at the newfound stretch of evening light, a whimsical musing bubbles to the surface: Is it time to retire this twice-yearly twist in our temporal fabric?

The genesis of this time-honoured tradition is as fascinating as time travel itself, dating back to Roman times and earlier. In modern times, originally adopted by countries to conserve energy during wartime, daylight saving time (DST) was a clever manipulation of the clock to extend daylight hours, thus saving on artificial lighting and conserving coal for the war effort.

Fast-forward through time, and the necessity of this practice is under scrutiny, much like a watchmaker inspecting the gears of a bygone timepiece. In an era where LED lights illuminate our nights with efficiency and renewable energy is on the rise, one can’t help but wonder if the original motivations behind DST still hold a candle to modern needs.

Yet, there’s an undeniable charm to this biannual clock-changing ritual, even if it’s not entirely synchronized where some countries don’t make the change at the same time as almost everyone else (especially looking at you, most of the USA and Canada).

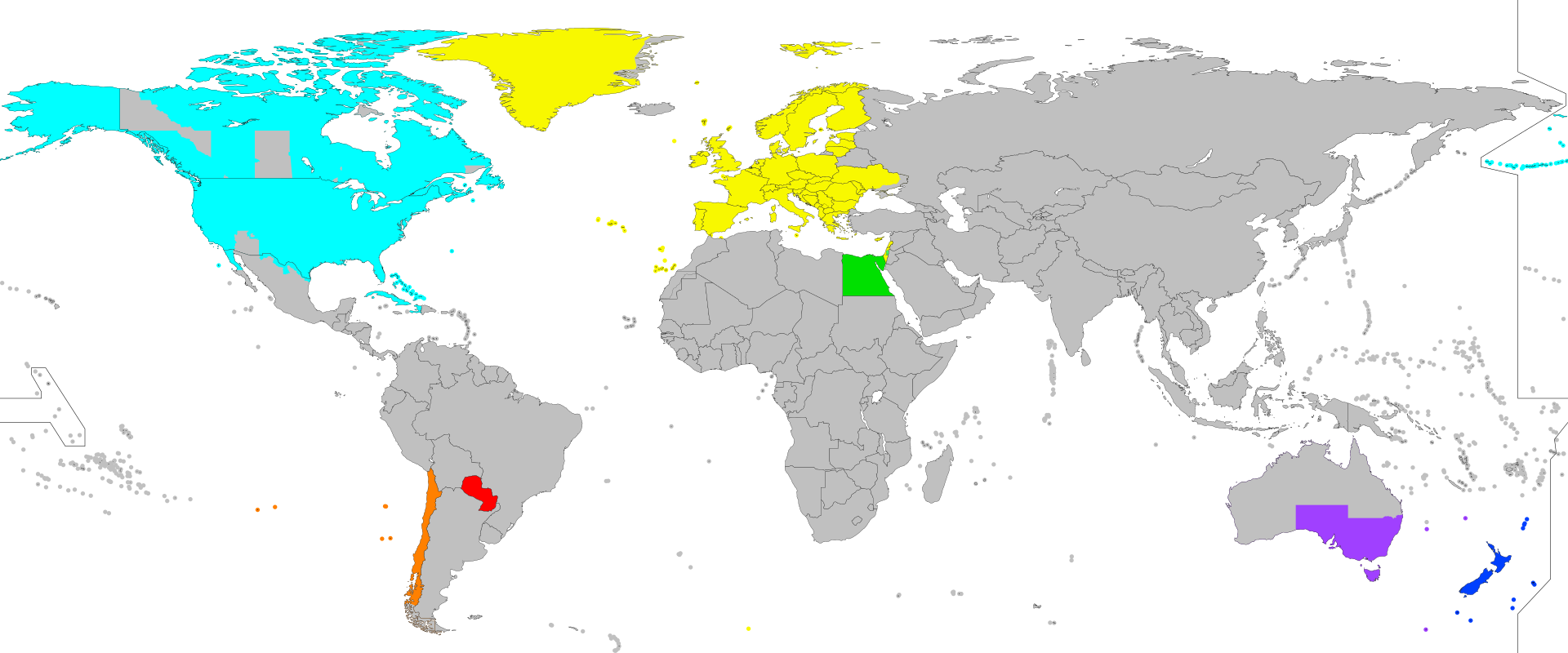

It’s a ritual mainly followed in North America and Europe (shown respectively in cyan and yellow in the map projection below), and Egypt and Palestine (green) in the Northern Hemisphere; and Chile, Paraguay, parts of Australia, and New Zealand in the Southern Hemisphere.

Perhaps more significantly, it’s not observed at all in the majority of the world’s countries, shown in grey on the map.

Still, where it is observed, it is a shared experience, a moment where we collectively grumble as we adjust our myriad devices (though, admittedly, many do it automatically), momentarily united in our bewilderment over “losing” or “gaining” an hour.

It’s as if the hands of our clocks are playfully reminding us of our human attempt to impose structure on the fluid concept of time.

However, as we navigate through the digital age with its 24/7 global economy, the calls to abolish the practice grow louder. The impact of DST on our health is no laughing matter, either, where disrupting our circadian rhythms is linked to myriad health risks, from increased heart attack rates to heightened stress levels.

And what of the economic benefits? The once-touted energy savings are now a topic of debate among experts, with some research suggesting the impact is minimal, if not counterproductive.

Dancing with Daylight

Despite these compelling arguments, there’s a certain magic to the long, luminous evenings that DST brings. It gifts us time to linger in the outdoors, enjoy leisurely walks, or simply sit and marvel at the extended daylight.

This tradition, with all its peculiarities and inconveniences, serves as a twice-yearly reminder of humanity’s endless quest to harness time, to adapt and mould it in a way that enriches our lives, even if just by providing more light to enjoy an evening stroll.

As we stand in the aftermath of our latest temporal adjustment, having already “sprung forward,” we’re invited to reflect on the future of this curious custom. Could we envision a world where our lives are not punctuated by these biannual adjustments, where time flows in unbroken continuity, more in sync with the natural world?

Until such a time arrives, we continue the tradition, partaking in this dance with daylight.

So, as we adjust to our newly acquired evening hours, let’s do so with a light heart and an appreciation for the quirkiness of human innovation. And perhaps, in this moment of collective adjustment, we can find comfort in the thought that while we may have temporarily “lost” an hour to DST, what we gain in daylight is a timeless treasure.