After nearly three weeks of protest in Cairo and other cities across Egypt, the end came quite quickly on Friday night so that, today, the country no longer has Hosni Mubarak running things and instead has the military in charge, at least for the time being.

The BBC has a pretty good analysis that makes it easy to understand the tumultuous if not historic events in that country since January 25.

A general view is that a catalyst for what happened in Egypt was what happened in Tunisia that led to the fall of the government and departure of that country’s president. Things came to a head far more quickly in Tunisia than in Egypt although the detailed circumstances in each country are different.

A general view is that a catalyst for what happened in Egypt was what happened in Tunisia that led to the fall of the government and departure of that country’s president. Things came to a head far more quickly in Tunisia than in Egypt although the detailed circumstances in each country are different.

Among media reporting as events unfolded in Egypt has been quite a bit of commentary (and speculation) concerning which countries in the Middle East could such unrest spread to. Who might be next, in other words.

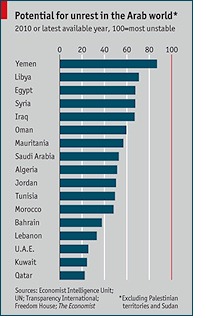

In The Economist this week, a briefing on Egypt and the region includes the chart you see here on the potential for unrest in the Arab world. What I find interesting about it is that Tunisia is far down the table in terms of likelihood of instability compared to Egypt. And there are two countries above Egypt, but nothing of note is reported there regarding civil unrest to alarm governments. Yet. The hot spots that might be next are Yemen and Libya, according to The Economist’s chart (and make sure you read the methodology on how The Economist calculated the ranking).

I suppose it illustrates just how difficult it is for outsiders to make credible predictions about the Middle East.

Something else I find interesting that adds to the mix of effort to better understand the dynamics of Middle Eastern societies is the role of modern communication technologies. I’m talking about the internet and communication tools like Twitter and Facebook, which many commentators, observers and pundits believe were instrumental in accelerating the speed of change that’s occurring in Tunisia and Egypt. Indeed, the Egyptian government was sufficiently concerned that they shut down access to the internet for a while as well as shutting down cellular (mobile phone) networks.

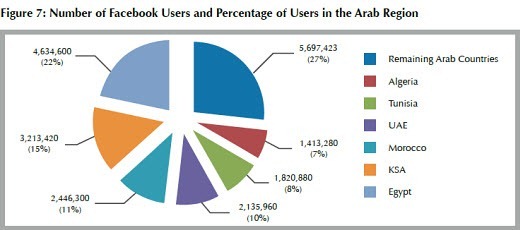

A few days ago, the Dubai School of Government (DSG) published the Arab Social Media Report which analyses data on Facebook users in all 22 Arab countries, in addition to Iran and Israel. Even if your interest in the Arab world is limited, the report makes for fascinating reading that gives you some insight into events that are shaping other societies and that will have an impact on yours and mine.

Consider this perspective about the report from the DSG:

[…] the penetration of social networking tools is soaring in the Arab world. The growth is highest among youth between the ages of 15 and 29, who make up around one-third of the total Arab population. The report states, for example, that the total number of Facebook users in the Arab world has increased by 78 percent, from 11.9 million in January 2010 to 21.3 million by December 2010, with 75 percent of the Facebook community in the Arab region belonging to this demographic and driving its growth.

And this commentary from the report itself is probably the one that helps you see exactly what effect “being connected online” actually means:

The civil movements in Tunisia and Egypt during December 2010 and January 2011 are a prime example of the growth and shift in social media usage by citizens. The proportion of Tunisian citizens connected through Facebook, for example (Facebook penetration), increased by 8% during the first two weeks of January 2011. The type of usage also changed markedly, shifting from being merely social in nature to becoming primarily political.

Yes, no wonder the Egyptian government tried to stop people using Facebook and anything connected to the internet.

There seems to be very little doubt that we will see more unrest in more Arab countries in the coming months. Whether we’ll see the downfall of regimes, and if such events happen peacefully or with much spilt blood, is very hard to predict.

As is the answer to the question: who’s next?

Related posts:

5 responses to “Which Arab state will be the next falling domino?”

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Geoff Livingston and Geoff Livingston, Robert Clay. Robert Clay said: RT @jangles: [nh.com] Which Arab state will be the next falling domino? http://goo.gl/fb/8Rkgn […]

[…] mention Which Arab state will be the next falling domino? — NevilleHobson.com — Topsy.com on Which Arab state will be the next falling domino?Which Arab state will be the next falling domino? — NevilleHobson.com on A moment in history from […]

[…] Which Arab state will be the next falling domino? (nevillehobson.com) […]

We need to stop talking dreamy nonsense. If Twitter was a revolutionary driver behind the protests in the Middle East, we have to explain how comes there are just 14 000 registered users of Twitter spread between Egypt, Tunisia and Yemen, which have a combined population of around 120 million. There are only around 1.5 million broadband connections in Egypt – pop 85 million. Most of those broadband connections function close to narrowband levels. They do not enable mass, simultaneous, interaction that any coherent real-time organisation requires to be meaningful as a mass form of communication during or even before a chaotic rebellion. Moreover, even mobile phone triple play connectivity, that we take for granted, is not yet a major factor in Egypt (so sharing videos is not really an option for the masses). I’ve posted three reality checks that highlight why we should avoid technological determinism and why we should give more credit to the Egyptian people. Here’s the most up-to-date of my posts:

http://paulseaman.eu/2011/02/new-muse-on-social-media-in-egypt/

[…] Which Arab state will be the next falling domino? (nevillehobson.com) […]