In 2020, I bought a Toyota Corolla Excel self-charging hybrid hatchback – known today as a hybrid electric vehicle (HEV) – and it has been a delight to drive. The welcome attributes of this car, such as exceptional fuel economy, low emissions, and Toyota’s renowned reliability, have made it an easy car to live with. The 10-year hybrid battery warranty is a reassuring bonus.

The self-charging hybrid approach championed by Toyota has always made sense to me: it captures energy through the internal combustion engine charging the battery, and from regenerative braking, rather than relying on external charging.

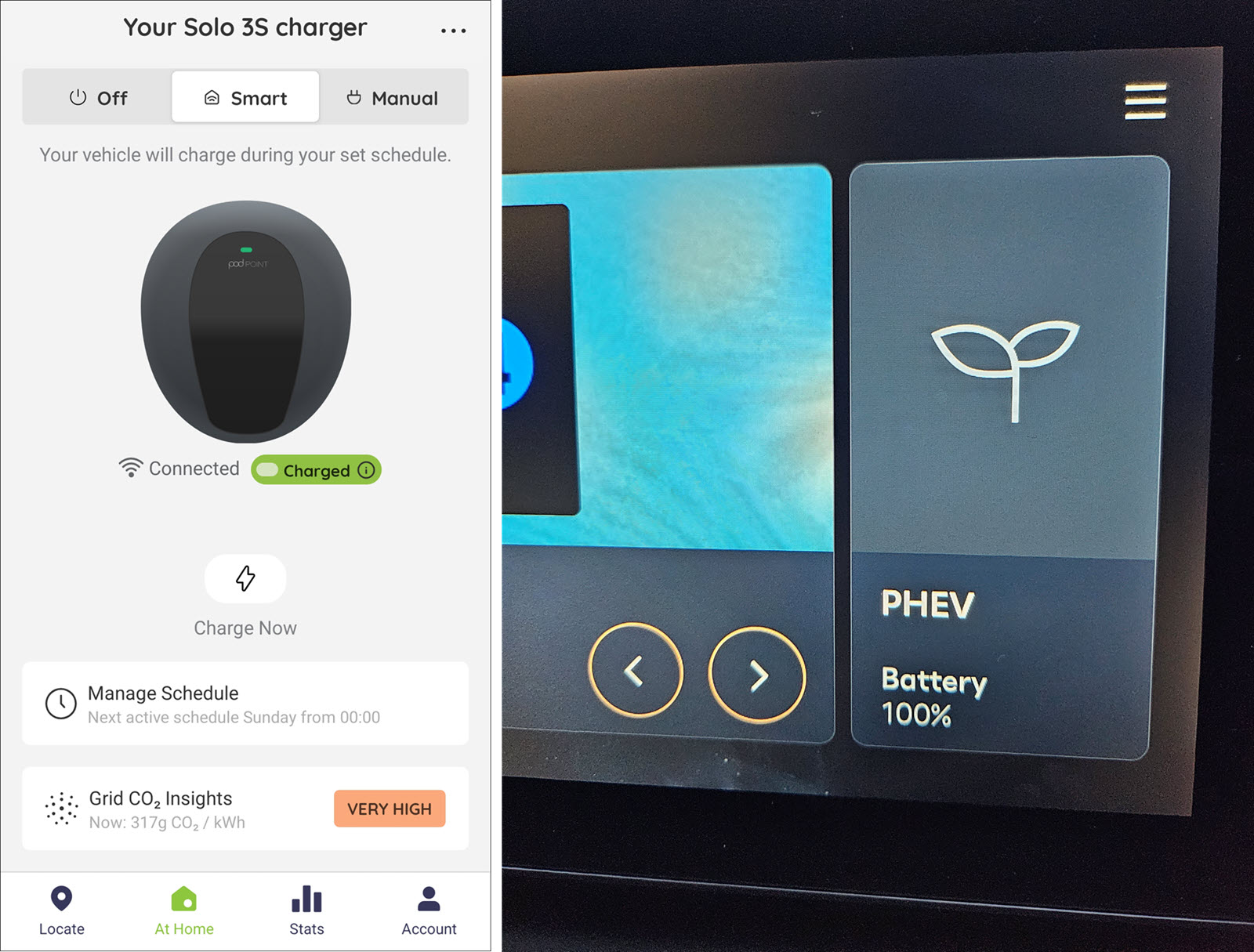

After a relatively minor accident in December (a bike rider fell off his bike and hit me), my car is now going in for repairs. In the meantime, on Friday, my insurance company provided a 2025 Hyundai Tucson Premium plug-in hybrid electric vehicle (PHEV) as a courtesy car, which I expect to have for a couple of weeks.

I’ve been getting to know the car a bit during the weekend. This is an opportunity I welcome because, while I understand the concept of PHEVs, I have long been sceptical about their practicality.

I’ve always considered hybrid technology a logical stepping stone towards an electric vehicle (EV), combining the efficiency and economy of an electric motor with the convenience of a petrol engine.

And I would add that while EVs are often seen as the ultimate goal for sustainable driving, this post focuses on hybrids as a transitional technology. My aim is to evaluate the practicalities and compromises of hybrids, not to compare them directly to EVs.

Are PHEVs the Best of Both Worlds or a Compromise?

My main concern with plug-in hybrids has always been the requirement for manual charging. Unlike my Toyota HEV, which seamlessly charges the battery on the go as determined by the car’s ECUs, a PHEV like the Hyundai requires plugging into a charging point.

Without regular charging, a PHEV becomes little more than a heavier petrol-powered car burdened by an underutilised battery. It seems inefficient at best and expensively counter-productive at worst.

For years, I’ve questioned whether PHEVs offer real-world benefits. Some drivers treat them like conventional hybrids, rarely plugging them in. This negates the very advantage they’re meant to provide: a useful electric-only range. Studies suggest that many PHEVs fail to meet their promised efficiency levels because they rely too much on their petrol engine.

But now, I have the perfect opportunity to put my scepticism to the test.

PHEV vs HEV: A Comparison

Rather than comparing the Hyundai Tucson and Toyota Corolla as vehicles, I want to focus on how their hybrid systems differ. Here’s a side-by-side look at the key differences:

| Feature | Plug-in Hybrid (PHEV) | Self-Charging Hybrid (HEV) |

|---|

| Battery Charging | Requires external charging via a plug to maximise efficiency | Charges automatically via the petrol engine and regenerative braking, with no external charging required |

| Electric-Only Range | Can drive a significant distance, typically 20–50 miles, on electric power alone. (The Hyundai Tucson can get a realistic 30-45 miles.) | Limited electric range: usually 1–2 miles at low speeds. (My Toyota Corolla can achieve about 5 miles in these conditions if driving under 20mph.) |

| Fuel Efficiency | Very efficient when driven mainly in EV mode; less so if the battery isn’t charged regularly | Consistently better fuel economy than petrol/diesel cars, but not as high as a well-used PHEV |

| Emissions | Near-zero emissions when driving in EV mode | Lower emissions than petrol cars but higher than a fully-charged PHEV |

| Performance | More powerful due to a larger battery and electric motor | Lighter and simpler system, leading to a more consistent drive |

| Convenience | Requires regular charging to get the best benefits; otherwise, it becomes a heavier hybrid | No need to plug in – just drive as you would a conventional car |

| Cost | More expensive to buy than a self-charging HEV | Typically cheaper than a PHEV and requires no charging infrastructure |

| Long-Distance Travel | Good for long trips, but less efficient if the battery is depleted | Works well for long distances without external charging – the petrol engine charges the battery as needed |

| Charging Infrastructure Needs | Needs a home charging point or frequent access to public chargers for best results | No charging infrastructure needed |

| Suitability for City Driving | Excellent – if charged regularly, it can operate as a full EV for some city/urban trips | Good – low-speed electric mode helps in stop-start traffic but relies on petrol more than a PHEV |

| Suitability for Motorway Driving | Less efficient if the battery is depleted; relies more on petrol at high speeds | Works well on motorways with seamless petrol-electric switching |

| Maintenance | More complex system with a larger battery, potentially higher maintenance costs | Simpler hybrid system, generally lower maintenance |

| Resale Value | Can hold value well if EV range remains competitive | Reliable resale value but may not be as desirable as full EVs in the long run |

| Government Incentives (depending on jurisdiction) | Often eligible for tax breaks and incentives if driven mainly in EV mode | Some incentives but typically lower than PHEVs or full EVs |

(Reference sources: ICCT, ICCT, ECIU, consumer.org.nz)

Some Expectations from the Hyundai Tucson PHEV

The Hyundai Tucson PHEV is larger and heavier than my Toyota Corolla HEV, but it’s well-equipped and offers a respectable electric-only range of around 30–45 miles, quite a bit more than the Toyota, depending on your driving style and other factors. That’s enough to cover the short trips I typically do these days if I commit to charging it properly.

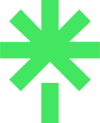

Fortunately, my new house has a 7 kWh PodPoint Solo S3 charger in the driveway, which I’ll use regularly to enable me to make the most of driving in EV mode. The house also has PV solar panels, but I’ve yet to figure out how the electricity generated from these might supplement home charging.

Here’s what I’ll be looking for during my test period:

- How often will I need to charge the vehicle? Will I find it convenient, or will it feel like a chore? Easy to do at home, but what about at a public charging point 20 miles away?

- What’s the real-world electric range? Will it live up to the advertised figures?

- How does the transition between electric and petrol feel? Will it be smooth and efficient, or will it feel like a compromise?

- What’s the overall driving experience like? Will the added weight and complexity affect performance and comfort?

- Will I change my mind about PHEVs? Can they genuinely offer the best of both worlds, or do they fall into an awkward middle ground? In other words, are they a stepping stone to full EVs, or are they an awkward compromise?

As I mentioned earlier, I’ve always seen hybrid technology as a transition phase towards fully electric vehicles, and my Toyota HEV’s self-charging system has made a strong case for itself.

EVs may represent the logical next step, but this post intentionally examines hybrids to explore their unique place in the transition to electrification. Plug-in hybrids occupy a different space in that transition. Are they a clever solution for those not ready for full EVs, or are they a compromised technology that only works if you commit to regular charging?

Over the next few weeks, I’ll aim to find out. I’ll then share my experiences – both the positives and the frustrations – and whether this PHEV experience changes my perspective.

Stay tuned for the follow-up!

(Photo at top via Adobe Express.)

Related Reading:

- Discussing Toyota’s Engine of Controversy (28 August 2024)

- Assessing the choice of self-charging hybrid cars vs EV (22 August 2022)

- The usefulness of single-journey data in a hybrid car (17 December 2021)

- Electric cars are coming, but where will you charge? (7 March 2020)